Lacing Through Time: A Corset’s Dual Legacy

Artikel

Corsets were worn by women starting from an early age. Up until the late 18th century, many parents believed it was possible to mold girls’ bodies into the fashionable silhouette of a narrowed waist. Wearing a corset provided breast and back support and gave women an upright, lifted posture. However, it was extremely harmful to health as it attempted to slim the waist through tight lacing, squeezing organs like the liver and lungs. Despite warnings from Dutch doctors, corsets remained in use until the early 20th century.

The different materials of the corset

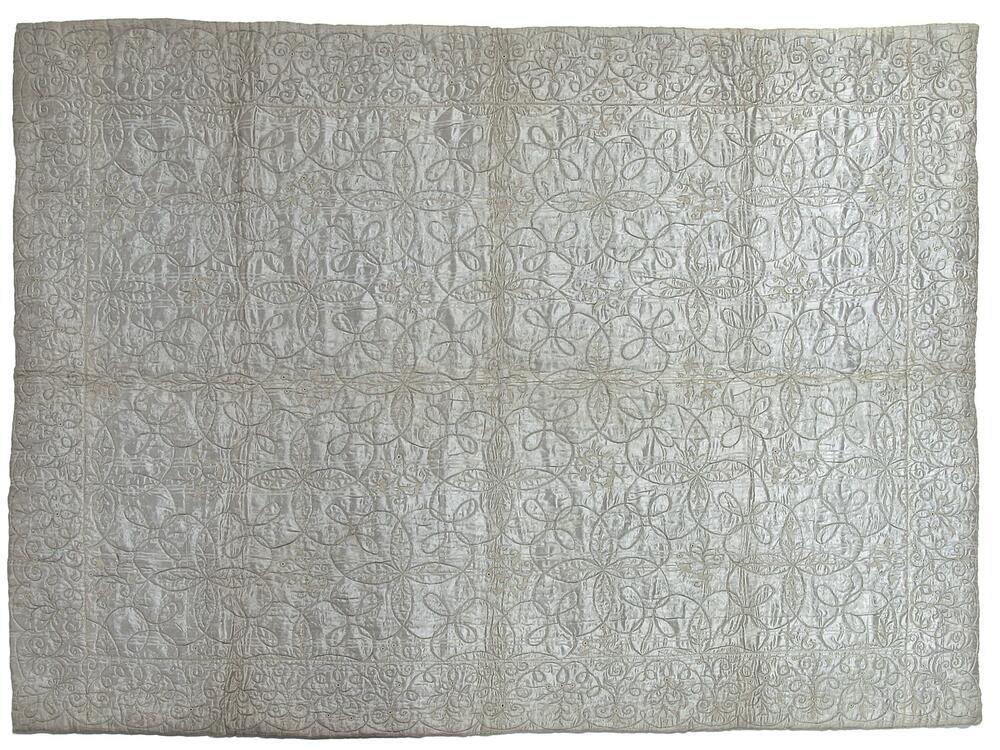

The corset is made using three materials: roughened white linen for the lining, whalebone (or baleen) for the filling, and green wool damask with a floral design for the outer layer.

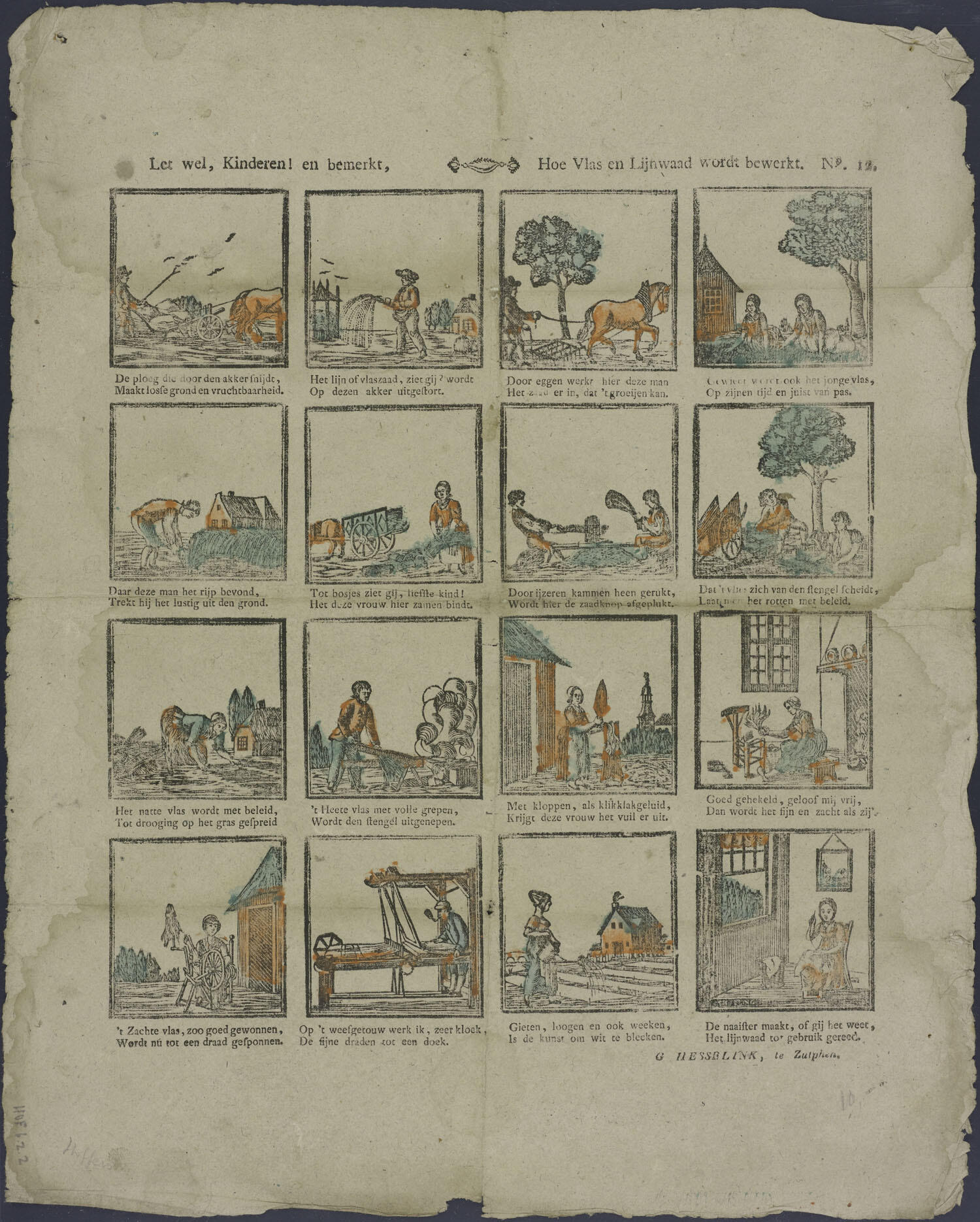

White linen was locally produced in the Netherlands during the 18th century. As a more affordable alternative to cotton, it became a commonly used material for clothing linings.

Damask comes in two varieties: wool and silk. Since silk was extremely expensive, it was only worn by the extremely wealthy. This corset is an example of wool damask, which was cheaper than silk and thus worn by more ordinary rich people. Damask was popular among the Zaans people during the 18th century, though the wool damask used in the Netherlands was imported from Norwich, England.

Whalebone, also known as baleen, has a rich history. It is a type of hair from the ‘beard’ of a baleen whale and contains the protein keratin, which is easily shaped with heat. Baleen was used in fashion from the mid-to-late 16th century and became increasingly popular for European corsets in the 18th century. Body warmth enabled the strips of baleen to shape themselves to the body, providing a more comfortable fit for the wearer. In the mid-18th century, the Zaan region was one of the most important whaling centres in Western Europe. However, overfishing led to a significant decline in whale populations, making baleen a costly luxury. By the early 20th century, baleen was replaced by synthetic plastics.

Two projects, two stories

This green damask corset was part of two interesting projects. The corset’s first debut was at the Plastic Crush exhibition at Wereldmuseum (formerly Tropenmuseum) Amsterdam from November 2022 until April 2023. The exhibition delved into our changing relationship with plastic, tracing its journey from early enthusiasm to modern-day worries about waste. It featured a blend of global and local narratives, museum artefacts, contemporary art, and iconic plastic objects, while also spotlighting young designers influenced by the museum’s collection.

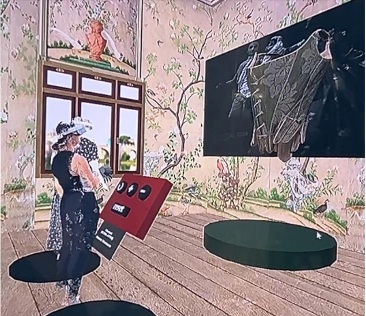

The second project was an innovative social VR installation called Fashion: Beneath the Skin, which took place at Beeld en Geluid in Hilversum from June 26-28, 2024. This VR experience displayed garments from the Central Museum Utrecht, Zaans Museum, and Kunstmuseum Den Haag that would otherwise remain unseen. Visitors were invited to explore the fashion shift of the 21st century from restrictive garments to those embracing natural body contours, influenced by societal changes such as women’s emancipation, body positivity, and technological advancements.

The green damask corset exemplifies 18th-century restrictive fashion, using whalebone to mold women's bodies into a desired silhouette. In contrast, the VR installation displayed the 21st-century shift towards garments that embrace natural body contours, highlighting the evolution from rigid designs to modern, inclusive practices.

The importance of different contexts

The fact that this corset was part of two different projects, each telling a unique story, highlights its richness as an object. Through the Plastic Crush exhibition, it illustrated the historical transition from natural to synthetic materials, while in the VR installation "Fashion: Beneath the Skin," it highlighted the evolution of fashion from restrictive to more body-positive designs. This duality indicates the intriguing ways in which the meanings of objects shift when placed in varying contexts. Examining these changes offers valuable insights into both our past and present cultural practices.

Aanvullingen